This week, starting on Sunday, marks the centenary of the Battle of Vimy Ridge, when the Canadian Corps, fighting together, achieved a significant victory on the Western Front during World War One. Vimy is often regarded as part of Canada’s coming of age as a post-colonial country, as this backgrounder in the New York Times explains.

Canadian historian Duff Crerar, an authority on Canadian chaplains in the Great War, has been regaling his friends with stories of how our padre ancestors supported the Vimy battle. I have collected his emails and images below and am happy to present them. MP+

Preparing for the Battle – 1

The First Canadian Division moved into its pre-Vimy quarters

around the old Chateau of Ecoivres in mid-March. In the upstairs hall rested a

large model of Vimy Ridge, which officers and men came through to study. In the

garden was a billet filled up with tall racks of bunk beds, packing in almost

1500 men, with a high platform at one end, from which Canon Scott gave nightly

lectures after the band played a brief concert. To keep morale up, he

encouraged written questions to be handed up to him which he would try to

answer in an uplifting way. The first night everyone had a good laugh at

Scott’s expense when the note was read aloud without previewing or censorship:

“When do you think this God dam war will be over, eh?” On April 4 the news came

the America had joined the Allies, which partially answered the question that

stumped him a few nights before.

trenches and headquarters, he often donned a private’s uniform, but still was

easily identified by his white hair and clerical collar. All around him he

noted the stacks of ammunition accumulating, pitying the horses which dragged

heavy loads until some died of exhaustion. At night the road to Arriane Dump

and the narrow plank road connecting it with the St. Eloi road was crowded with

trucks, wagons, limbers, horses and men crowding each other in the blackout and

often forcing each other off into the deep mud on either side. Through the

tumult and furious cursing in the darkness the Senior Chaplain would make his

way, joking that the horses and mules, at least, could not understand the

profanity directed at them.

shrine with canvas over the windows, which he dubbed “St. George’s Chapel”.

Each morning at 0800 he celebrated Holy Communion, with the troops standing in

and around the altar. Underneath a shell-battered crossroads named Maison

Blanche, a large cavern sheltered one of the battalions in reserve, where Scott

would drop in to hold services. Scott was famous for breaking up gambling when

he encountered it, but one night men of the 16th, holding hot cards,

promised to come if he let them finish their hand. After announcing that he

would hold the service until the game was over, almost everyone there joined

the service.

occasionally let loose, carefully seeking out their future targets, and

startling bystanders not aware of their well-camouflaged hideouts. But enemy

fire could still strike the best-concealed by chance. Canadian Railway troops

died when a German shell hit their billets. Scott buried eleven of them on the

hillside.

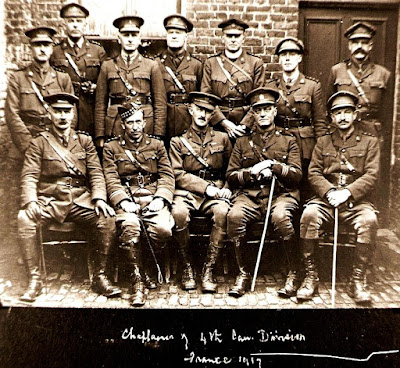

From the Report of Major A.M. Gordon, Sr. Chaplain, 4th

Canadian Division dated 17 March, 1917

worship parades in 4th Division. During the trench raids in

preparation for the main attack all his chaplains have been either in battalion

Headquarters or Advanced Dressing Stations. Other chaplains maintained Chaplain

Service coffee stalls where hot drinks were dished out to the men going forward

or coming out of action. During the raid on 15 March, Chaplain George Farquhar

served at the Regimental Aid Post with the Medical Officer, at the request of

both the battalion commander and the M.O.

Quartermaster General, Canadian Corps, requesting sites for Chaplain Service

Coffee Stalls directly on the routes to be taken by the troops of 4. Canadian

Division during the Vimy Attack, in areas relatively safe from shelling.

(Report by Major the Rev. A.M. Gordon, 4 Div. Sr. Chaplain)

-

3 Protestant chaplains at the RAPs, 1 Protestant

at the Advanced Dressing Station on the Arras Road, 2 Roman Catholic chaplains

at relay point for ambulances and stretcher bearers, Two Protestant chaplains

at the Main Dressing Station # 11 Canadian Field Ambulance, with two Roman

Catholic chaplains alternating duty there for round the clock coverage. One

Protestant chaplain will cover the #12 Field Ambulance, while one will serve as

spare for coffee stall, burial party and battalion coverage. Gordon leaves his

most junior chaplain in the office and goes forward to supervise and assist in

the 4th Divisional front line area.

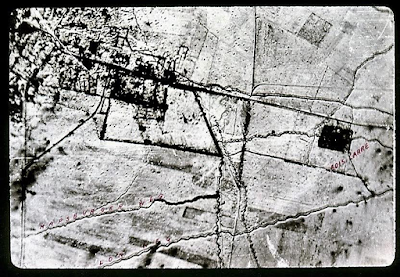

The Chaplains of the 2nd Division left extensive reports which can be matched with contemporary trench maps and aerial photographs to demonstrate how they followed the attacking troops, setting up aid posts and working with casualties in captured dugouts and trenches. D.E. Robertson’s report begins with jumping off with the second wave of attackers, accompanying medical officers and others setting up advanced posts on the far side of Thelus. From 1400 onwards Robertson and a Medical sergeant operated an advanced aid post in a dugout in Bois Carre, which treated men coming in from many battalions, and many wounded Germans as well. Robertson scrounged rations and a German camp stove and was able to provide hot and cold drinks to the wounded and the stretcher bearers. He stayed on in the dugout through the next few days “During all the time, I tried to speak a word of comfort or offer a prayer with the wounded. I took the names of home folks, and any messages they wished me to send. This meant writing scores of letters. Near Bois Carre I established a cemetery primarily for the 4th battalion, It has been recognized by the Graves Registration Commission. I buried twenty six men belong to the 14 and 31st Battalions, and of the Trench Mortar Battery. On the night of the 12th we moved back to the old German front line. “ The return was complicated by he and eight others taking turns bringing back a wounded German they had found in the bottom of a trench, nearly frozen The mud was so deep that it took several hours to get the man under shelter. Looking back, he noted that every soldier he had personally greeted the night before the attack had either been killed or had passed by him, smiling but wounded, going the other way after the battle.

A moving post.

Very moving indeed