It’s been very quiet here since Christmas. In my spare time, when not working or helping my wife’s battle with cancer, I’ve been focusing on my hobbies, which are described in my other blog here.

However, I did write a piece in December at the invitation of the Friends of Fort York, which preserve the historic war of 1812-era British fortification in Toronto.

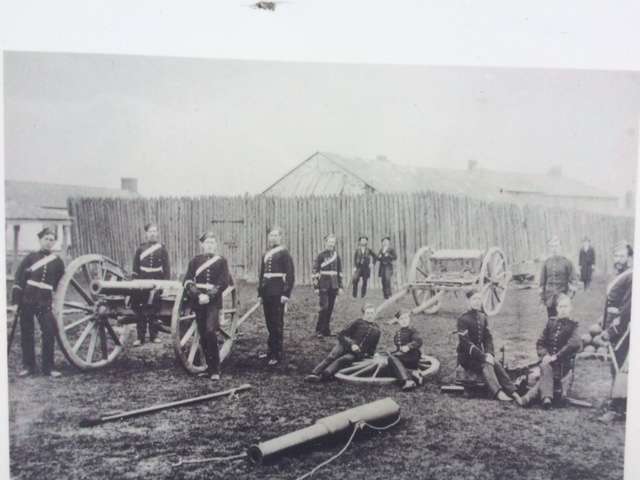

Pedestrian entrance to Fort York off of Bathurst Street. The Gardiner Expressway, visible to the left, and the condo towers in the background, show how Toronto has grown since the early 1800s and how the lakeshore has been pushed back. In its heyday, Fort York lay on the shore of Lake Ontario.

Given my slight expertise in military religious history, I was asked to write a piece on religion at the fort in the 1800s, a difficult subject given that so much of lived religion (actual beliefs and practices) is not nearly as well documented as is official religion (formal church history).

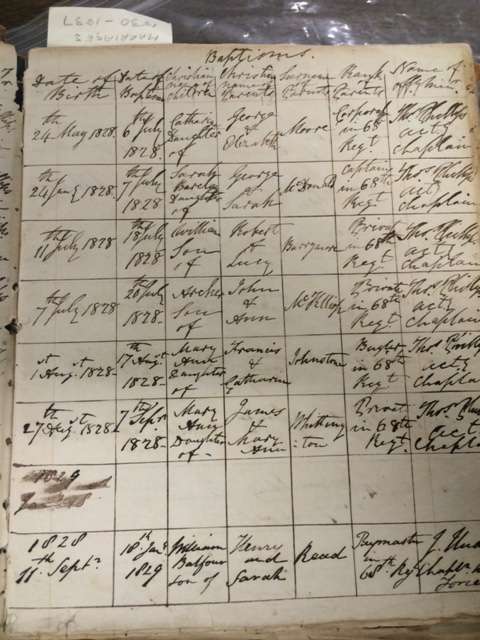

While not an extensive piece of original research, I did get to look at some of the Toronto diocesan archives which show births, baptisms, weddings and funerals at the Fort, as well as some other original source material.

Baptismal register showing christenings of children born to military families of the British Army’s 68th Regiment in 1828, and signed by the acting garrison chaplain.

It is impossible to generalize about lived religious life on the basis of the documents available to us. While the British redcoat had a reputation as being foul-mouthed, drunken and irreverent. While this may be true then as now of some soldiers, this stereotype ignores the influence of Methodism, missionary movements and Christian welfare organizations that actively reached out to British soldiers throughout the empire. The stereotype also ignores the role of religion in the lives of Roman Catholics, Presbyterians and various non-conformers whose spiritual needs were not met by official military chaplains, who were almost entirely Anglican. It is also impossible to generalize as to how official religion — the round of church parades, weddings, christenings and funerals — was received by soldiers. To some, official religion may have been an irritant, but to others it may have been a reassuring if seldom thought of part of life.

My conclusion in the article is thus that “While the average soldier may have been more comfortable in a tavern than on church parade, he may also have been more devout than is commonly supposed.”

The article begins on page 3 here.

Good article. Diaries and other personal accounts are fascinating and informative. Far too few for the lower ranks. I trust you know about Private Henry Hook VC and how different he was form his depiction in Zulu?