Preached at All Saints, Collingwood, and St. Luke’s, Creemore, Anglican Diocese of Toronto, Remembrance Day Sunday, 13 November, 2022. Texts: Wisdom of Solomon 3:1-9; Psalm 116:1-8; 1 Peter 1:3-9; John 11:21-27

“But the souls of the righteous are in the hand of God, and no torment will ever touch them. In the eyes of the foolish they seemed to have died … but they are at peace” (Wis 3.1)

What should the church say on this day, on Remembrance Day Sunday? Should we say anything different from what we pray and proclaim on any other Sunday?

I ask these questions because I worry that if we’re not careful, we run the risk of being whipsawed theologically, so that our message becomes incoherent. After all, just last Sunday we heard Jesus tell us to love our enemies and to turn the other cheek (Lk 6:27-29). Today, it’s tempting to say something radically different, to speak of “our glorious dead” and to want to give thanks for their victories in battle.

It may be impossible to avoid some incoherence on Remembrance Day Sunday. There is wide variation in the Christian witness on war and the gospel, ranging from the pacifism of the Mennonite tradition to the Just War theology of the Roman Catholic tradition, which justifies war in certain circumstances. In my own experience as a military chaplain I was forbidden to carry weapons because it’s long been felt that Christian ministers can serve in uniform, but only as non-combatants. So since we as Christians have never fully agreed on how we can reconcile the gospel of Jesus Christ with war and violence, I think some caution is called for.

In that spirit of caution, I think the first, the best, and the safest thing we need to say today is that “we remember”.

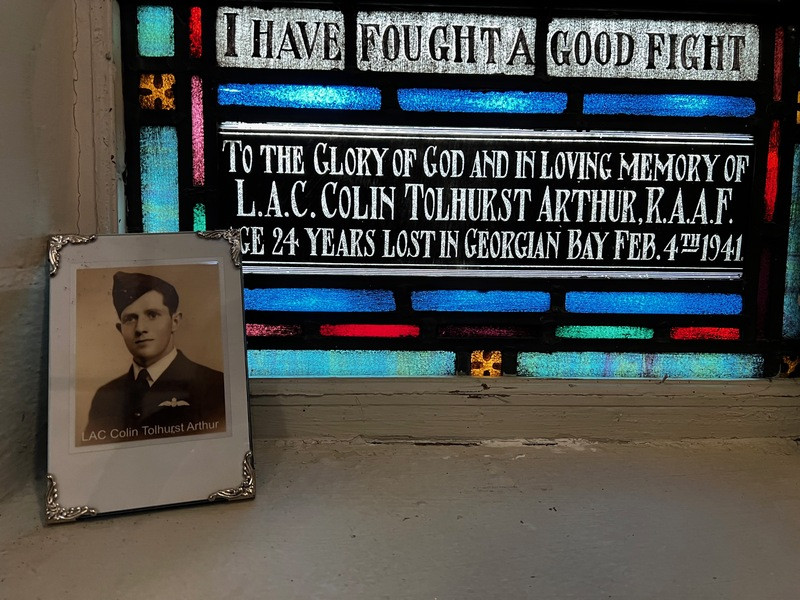

We remember those of this parish who served and particularly those who never came home. We remember those of this community, an incredible 1 in 10 of Collingwood’s population who left for the First World War, just as we remember the men and women who in the Second World War built the corvettes that left here to help keep the sea lanes open. Likewise remember those from across the Commonwealth who came here to learn to fly in the British Commonwealth Air Training Program. Of that later group, we have a special duty to remember our Australian friends, Colin Arthur and Claude Ross, who are honoured at the back of our nave, just two of the many fledgling flyers who died in training. And of those who did train here in Canada and then went to fly in the deadly skies over Europe, we remember the almost ten thousand Canadian airmen killed in the bomber raids over Nazi Germany. Likewise we remember those who served in peacekeeping where it worked, as in Cyprus, or where it disastrously failed, as in Bosnia and Rwanda. We remember those who went to Afghanistan with all the tragedy of its outcome, and who today wrestle with memories of lost comrades and who bear wounds, visible and otherwise.

So the first thing the church can say on Remember Day is we accept the duty of memory. To Edward Knight, who is remembered on the wall across from this pulpit, and to Colin Arthur and Claude Ross and all those others, we say remember you as best we can. We pledge to you that we will learn your stories and teach them to the generations that follow, that we will honour your sacrifices, and that we will do our best to see that you did not die in vain. All of these duties and obligations are laid on our shoulders when we say, as many did at the cenotaph on Friday, “we will remember them”.

This duty of memory is a civic duty, cor we as Christians and Anglicans are called to remember just as Canadians of all faiths and none are called to remember. Fair enough. We want to be good citizens and good Canadians, we want to be found worthy of those who went before us. But as Christians, our memory is nuanced, it must have theological layers if it is to be worthy of the gospel. If we remember the ten thousand Canadians who died flying with Bomber Command, then we must also remember those in the cities they bombed, just as we remember the civilian dead of all the cities, Warsaw, London, Coventry, Dresden, Kyiv, Kherson. We must remember the totality of modern war, how it consumes countless lives, military and civilian, and how war is perhaps the most sinful thing we can name in the world. We must remember with sorrow as well as pride, with repentance as well as patriotism. If there is one day of the Christian year that should teach us how to think of war, then that day is surely Ash Wednesday.

Beyond saying that we remember, I think that on this day, Remembrance Sunday, the church must be sparing with our words and careful of how we speak about God’s purposes. In our first lesson, from the Wisdom of Solomon, we heard that “But the souls of the righteous are in the hand of God, and no torment will ever touch them. In the eyes of the foolish they seemed to have died … but they are at peace” (Wis 3.1). This text from the Hebrew scriptures offers the comfort that the dead we remember are in the care of God (indeed, the scripture readings for Remembrance Sunday are the very ones we use for All Souls, our feast for the faithful dead), but we need be extremely careful with our use of the word “righteous”. In the context of our readings, our first lesson can seem to say that our war dead and the causes they fought in were righteous, but this would be to speak in human terms. When scripture uses the word “righteous”, it is always speaking of the goodness and rightness that is God’s only, and only God can make us righteous.

Even so, it is in the nature of soldiers to want to believe that they fight in a righteous cause. Let me explain by describing a conversation that I often think of. I have a friend who as a young Army officer had served in Afghanistan. He was deeply effected by his experience, and on his arm he had tattooed the names of two of his soldiers who were killed on their tour. Over a beer in the mess one day, he told me how much he appreciated the chaplains, or padres, that he had met over there, but he said he had one complaint. “Why don’t you padres ever pray for a good smiting?”

A little confused, I asked him what he meant. He told me, “Before we went out on a mission, the Padre would pray for our safety and that God would bless us and bring us back whole, and that was nice, but what I really wanted was for that Padre to pray for God to help us smite our enemies like God smites people in the Bible. But he never prayed that. I like Padres, but why can’t you guys pray for a good smiting?” The word “smite” (Her nawkaw) of course is a King James Bible word meaning hit, kill, or destroy, and is often used in the bloodier books of the Hebrew scriptures when God encourages his people to kill their foes.

I told my friend that my chaplain colleague was probably wise enough to know that such a prayer would have been wrong. Think about it, I told him. Somewhere out there in the darkness, while you were getting ready to go out on your patrol, don’t you think there might have been another holy man praying that Allah would give his guys the strength to kill you, the infidel invader? If your padre had prayed for you to kill in God’s name, would that have made him any better than the Taliban holy men who promise a speedy trip to paradise for warriors and martyrs?

I was trying to convey to my young friend the inherent dangers in thinking of ourselves as holy warriors in a holy cause. Such a mindset allows for our worst, most violent selves to emerge. Only God is righteous, and only God can make us righteous, and if God is love, then God cannot be war. It may be that some wars must be fought because they are necessary. The Ukrainian war of self-defence is perhaps the clearest case for a just war that I have seen in my lifetime. I know for certain, because I’ve met them, that there are Ukrainian army chaplains who see their cause as righteous, even holy. I cannot speak for them, and I would not presume to correct them. Perhaps all we can do is to remember the dead of Bucha and Kharkiv and Kherson, and can pray that God delivers Ukraine and makes possible a lasting and just peace. Beyond that, I don’t know that the church has anything to say.

So we fall back on three words, “we will remember”. We remember with penitence just how seductively easy wars are to start, and how hard they are to stop. We remember with sorrow the dead, those of this parish, of this country, of this modern age and its terrible demand for sacrifice. In our sorrow, we commit those we remember as best we can into the eternal memory of God, to whom none are lost, none are forgotten. And we remember the promise of the resurrection, in the sure and certain hope that Christ who raises the dead will return to end our wars and the sorrow of our wars. We remember these things.