No Canadian

scholar knows the history of Canadian military chaplaincy in the Great War

better than my friend, Dr. Duff Crerar.

In these notes which Duff kindly shared with myself and CAF chaplain

colleagues, Duff describes the ministry of Canadian padres in the last months

of the war and on to demobilization. It

is a harrowing story of chaplains pouring themselves into their work and in

some cases working themselves to death.

My thanks to Duff for telling their stories. MP+

scholar knows the history of Canadian military chaplaincy in the Great War

better than my friend, Dr. Duff Crerar.

In these notes which Duff kindly shared with myself and CAF chaplain

colleagues, Duff describes the ministry of Canadian padres in the last months

of the war and on to demobilization. It

is a harrowing story of chaplains pouring themselves into their work and in

some cases working themselves to death.

My thanks to Duff for telling their stories. MP+

The Pursuit

to Mons and the Padres

to Mons and the Padres

The Canadians

captured Cambrai on 9 October, having again surprised the Germans by a night

attack. Already attempting to make a general withdrawal, the enemy gave way

before they could blow all the critical bridges. The Second Division’s 20th

and 21st Battalions saw off a surprise counter-attack by German

tanks, but it was clear that the Germans were making another retreat.

captured Cambrai on 9 October, having again surprised the Germans by a night

attack. Already attempting to make a general withdrawal, the enemy gave way

before they could blow all the critical bridges. The Second Division’s 20th

and 21st Battalions saw off a surprise counter-attack by German

tanks, but it was clear that the Germans were making another retreat.

The

Canadians had broken through at the critical point of the Siegfried line. Valenciennes was the next fallback for an army

rapidly running out of men. Over twenty German divisions were disintegrating because

they could not be reinforced. Crown Prince Rupprecht doubted that his troops

would hold to December.

Canadians had broken through at the critical point of the Siegfried line. Valenciennes was the next fallback for an army

rapidly running out of men. Over twenty German divisions were disintegrating because

they could not be reinforced. Crown Prince Rupprecht doubted that his troops

would hold to December.

The chase

was one. Canadians would bombard a German position, patrols would investigate,

and report the Germans gone or in the process of leaving. Or, there would be a

hurricane of machine gun fire, shrapnel and high explosive. Currie ordered his

troops to proceed with caution, especially as the trail of sabotage and

scorched earth combined with heavy rain to make casualty evacuation almost

impossible. The Allies were outrunning their supply lines. Canadian soldiers, enjoying

the experience of being greeted as liberators, were pausing for impromptu civilian

hospitality. Belgians were handing out much of their precious hoarded food,

which meant the Canadians had to rush some of their own rations forward to feed

the over one hundred thousand liberated civilians.

was one. Canadians would bombard a German position, patrols would investigate,

and report the Germans gone or in the process of leaving. Or, there would be a

hurricane of machine gun fire, shrapnel and high explosive. Currie ordered his

troops to proceed with caution, especially as the trail of sabotage and

scorched earth combined with heavy rain to make casualty evacuation almost

impossible. The Allies were outrunning their supply lines. Canadian soldiers, enjoying

the experience of being greeted as liberators, were pausing for impromptu civilian

hospitality. Belgians were handing out much of their precious hoarded food,

which meant the Canadians had to rush some of their own rations forward to feed

the over one hundred thousand liberated civilians.

The Germans

had not all given up. Postwar critics who charged Currie with needless

casualties in the last week of the war were oblivious or unwilling to

acknowledge that German machine guns and artillery continued to oppose the

advance, and that in many sectors local counter-attacks required continued

operations. The Germans gave every intention to fight for Valenciennes,

flooding the defences along the Canal de l’Escaut, with five –understrength – divisions

guarding the gateway, Mount Houy. Rebuffed when he offered his artillery assets

to assist the British, Currie grimly knew (after the British failed to take

Mount Houy for the third time) that his troops would have to take the hill, and

ruffled more than a few British senior officers by refusing to throw his troops

in without full preparations. He and Andrew McNaughton, his gunnery expert,

honoured their vow to purchase victory with shells, not men.

had not all given up. Postwar critics who charged Currie with needless

casualties in the last week of the war were oblivious or unwilling to

acknowledge that German machine guns and artillery continued to oppose the

advance, and that in many sectors local counter-attacks required continued

operations. The Germans gave every intention to fight for Valenciennes,

flooding the defences along the Canal de l’Escaut, with five –understrength – divisions

guarding the gateway, Mount Houy. Rebuffed when he offered his artillery assets

to assist the British, Currie grimly knew (after the British failed to take

Mount Houy for the third time) that his troops would have to take the hill, and

ruffled more than a few British senior officers by refusing to throw his troops

in without full preparations. He and Andrew McNaughton, his gunnery expert,

honoured their vow to purchase victory with shells, not men.

On 1

November, the all-Canadian attack blasted the Germans out of Mount Houy: the

shattered survivors surrendered to a mop-up attack by the 10th Canadian Brigade.

The 12th Brigade entered Valenciennes, and on 3 November the city was declared

free of German defenders.

November, the all-Canadian attack blasted the Germans out of Mount Houy: the

shattered survivors surrendered to a mop-up attack by the 10th Canadian Brigade.

The 12th Brigade entered Valenciennes, and on 3 November the city was declared

free of German defenders.

Canadian troops in Valenciennes after its capture on 3 November, 1918.

By then, General

Ludendorff, de facto commander in

chief of the German Army, had been dismissed. Attacks by Australians and

Canadians on 4 November struggled to mop up the snipers and machine gunners

left behind to cover the all-out retreat. The casualty rate plummeted, but

Canadians felt them even more deeply as it was clear that war was almost over.

It is a terrible thing to die at the end of a war. Most important, both to

Currie and his Army Commander, General Horne, was the reality that German

soldiers were not all giving up, but often continuing to cause casualties in

pockets of determined resistance. The Germans gave every indication they would

fight for Mons. Currie’s plan to encircle it and break in simultaneously fell

afoul of such isolated pockets of the enemy. On 10 November, a company of the

RCRs and another of the 42nd Battalion moved in to clear out Mons. After

causing a few last minutes casualties, the Germans melted into the mist. At

eleven, the Armistice took effect. Already a riotous celebration was brewing up

in the city centre. It was St. Martin of Tours day, the patron saint of

chaplains.

Ludendorff, de facto commander in

chief of the German Army, had been dismissed. Attacks by Australians and

Canadians on 4 November struggled to mop up the snipers and machine gunners

left behind to cover the all-out retreat. The casualty rate plummeted, but

Canadians felt them even more deeply as it was clear that war was almost over.

It is a terrible thing to die at the end of a war. Most important, both to

Currie and his Army Commander, General Horne, was the reality that German

soldiers were not all giving up, but often continuing to cause casualties in

pockets of determined resistance. The Germans gave every indication they would

fight for Mons. Currie’s plan to encircle it and break in simultaneously fell

afoul of such isolated pockets of the enemy. On 10 November, a company of the

RCRs and another of the 42nd Battalion moved in to clear out Mons. After

causing a few last minutes casualties, the Germans melted into the mist. At

eleven, the Armistice took effect. Already a riotous celebration was brewing up

in the city centre. It was St. Martin of Tours day, the patron saint of

chaplains.

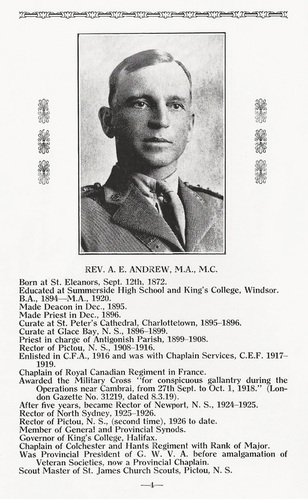

Canadian

chaplains had kept pace with the troops, though 3rd Division Senior

Chaplain Louis Moffit reported that holding services and large gatherings fell

by the wayside in the constant shifting and shelling. Reports preserved from

this period in Chaplain Service records are few. Another half-dozen chaplains

were wounded by shells. Father T. McCarthy had been with the 7th

Brigade constantly, and was reported among the first troops entering Mons. Conditions had been brutal, and more than one

padre could not express what they had seen in genteel tones. A.E. Andrew, an Anglican chaplain to the Royal Canadian Regiment, recently awarded the Military Cross for his work

with casualties (including stepping in when most of the officers had been

killed or wounded) in October, let off steam during the celebrations that

followed, making some frank comments about the high command which got into the Canada Gazette. The Assistant Director

of the Service, A.H. McGreer, noted “he used language which is commonly

employed by officers of all ranks, and I am sure he never dreamed of all his

statements being reported… If it comes to a court martial they can’t convict

him, I’m sure of that… Andrew got the MC the other day…” Word of Andrew’s

remarks at Cambrai, when told that he did not belong up front – “if the men can

go, I can” – had percolated through the Division. After they had cooled down,

the authorities let him off with a warning, and a transfer.

chaplains had kept pace with the troops, though 3rd Division Senior

Chaplain Louis Moffit reported that holding services and large gatherings fell

by the wayside in the constant shifting and shelling. Reports preserved from

this period in Chaplain Service records are few. Another half-dozen chaplains

were wounded by shells. Father T. McCarthy had been with the 7th

Brigade constantly, and was reported among the first troops entering Mons. Conditions had been brutal, and more than one

padre could not express what they had seen in genteel tones. A.E. Andrew, an Anglican chaplain to the Royal Canadian Regiment, recently awarded the Military Cross for his work

with casualties (including stepping in when most of the officers had been

killed or wounded) in October, let off steam during the celebrations that

followed, making some frank comments about the high command which got into the Canada Gazette. The Assistant Director

of the Service, A.H. McGreer, noted “he used language which is commonly

employed by officers of all ranks, and I am sure he never dreamed of all his

statements being reported… If it comes to a court martial they can’t convict

him, I’m sure of that… Andrew got the MC the other day…” Word of Andrew’s

remarks at Cambrai, when told that he did not belong up front – “if the men can

go, I can” – had percolated through the Division. After they had cooled down,

the authorities let him off with a warning, and a transfer.

W. B. Carleton, a priest from Metcalfe,

Ontario, received a surprise when the French Army conferred the Croix de Guerre

for his intrepid work with the 3rd Division Artillery. Carleton

would return as a Senior Chaplain to the Canadian Army in 1940.

Ontario, received a surprise when the French Army conferred the Croix de Guerre

for his intrepid work with the 3rd Division Artillery. Carleton

would return as a Senior Chaplain to the Canadian Army in 1940.

Other

chaplains were showing signs of strain as the pressure of operations turned

into the march to occupation across the Rhine and restlessness to get home.

Sickness, nervousness and other disorders were reported by several padres:

chronic bronchitis, a sign of exhaustion, and hard to treat in the

pre-anti-biotic era. His Brigade reduced to a skeleton by casualties, B.J. Murdoch

was returned to Britain on sick leave, exhausted and insomniac. He was given

early discharge and returned to New Brunswick, though the psychological scars

of being under fire relentlessly in the last 100 days would haunt him for the

rest of his life. Almond learned that one of his former chaplains, Salvation

Army officer Charles Robinson, who had reverted to combatant ranks in 1916 and

been awarded a Military Cross at Vimy Ridge, had been killed in September and

was buried near Arras. Just previously word had reached headquarters that a

Methodist Chaplain, Eric Johnston, who had been in action continuously with the

Canadian Machine Gun Battalion since Amiens, trying to spend a week with each company

across the Corps, had been evacuated sick to #20 General Hospital, where he

died of pneumonia.

chaplains were showing signs of strain as the pressure of operations turned

into the march to occupation across the Rhine and restlessness to get home.

Sickness, nervousness and other disorders were reported by several padres:

chronic bronchitis, a sign of exhaustion, and hard to treat in the

pre-anti-biotic era. His Brigade reduced to a skeleton by casualties, B.J. Murdoch

was returned to Britain on sick leave, exhausted and insomniac. He was given

early discharge and returned to New Brunswick, though the psychological scars

of being under fire relentlessly in the last 100 days would haunt him for the

rest of his life. Almond learned that one of his former chaplains, Salvation

Army officer Charles Robinson, who had reverted to combatant ranks in 1916 and

been awarded a Military Cross at Vimy Ridge, had been killed in September and

was buried near Arras. Just previously word had reached headquarters that a

Methodist Chaplain, Eric Johnston, who had been in action continuously with the

Canadian Machine Gun Battalion since Amiens, trying to spend a week with each company

across the Corps, had been evacuated sick to #20 General Hospital, where he

died of pneumonia.

Other padres

found the change in moral climate and the breakup of units for repatriation

seemed calculated to undo their work. Roman Catholic chaplains went to the

Belgian hierarchy as well as the British Army authorities to fight a soaring

V.D. rate. F.G. Sherring, a decorated Anglican Chaplain, exploded in rage when

his 2nd Division Artillery units were scattered, ruining his plans

to distribute comforts ranging from cigarettes to underwear — as well as his

Christmas and New Years’ religious services. Fortunately for him, his

near-seditious remarks about the high command were expressed in reports to his

chaplaincy superiors, who quietly filed them away without action or comment.

found the change in moral climate and the breakup of units for repatriation

seemed calculated to undo their work. Roman Catholic chaplains went to the

Belgian hierarchy as well as the British Army authorities to fight a soaring

V.D. rate. F.G. Sherring, a decorated Anglican Chaplain, exploded in rage when

his 2nd Division Artillery units were scattered, ruining his plans

to distribute comforts ranging from cigarettes to underwear — as well as his

Christmas and New Years’ religious services. Fortunately for him, his

near-seditious remarks about the high command were expressed in reports to his

chaplaincy superiors, who quietly filed them away without action or comment.

Throughout

the rest of the winter and early spring of 1919, the Canadian chaplains

prepared for the peace. Many occupied themselves in teaching in the Khaki

University, and some took advantage of the program to add to their own

education. Nearly two dozen made the journey to Buckingham Palace to receive

decorations from King George V. Often

they ran into chaplains of other denominations which they had served alongside,

and which they might never see, much less work with again. John Holman

reminisced about urgently throwing up sandbags alongside a priest to protect an

advanced dressing station before taking heavy fire, both in their shirtsleeves

in the Amiens heat. Many took part in the conferring of battalion colours, now

being brought over from England or being consecrated for the first time, in

drumhead services in Germany and Flanders. Others found themselves, in moments

of inactivity, thrown back to moments which they had pushed into the back of

their minds during the victory autumn. They saw faces. They recalled brief,

intense, often whispered confidences. They remembered the men they had helped,

many, to die. Percy Coulthurst, Ewen MacDonald, Thomas McCarthy, Canon Scott

just out of hospital in England and W.H. Sparks flashing back to ministering,

stretcher to stretcher, reciting, “The Lord is my Shepherd”.

the rest of the winter and early spring of 1919, the Canadian chaplains

prepared for the peace. Many occupied themselves in teaching in the Khaki

University, and some took advantage of the program to add to their own

education. Nearly two dozen made the journey to Buckingham Palace to receive

decorations from King George V. Often

they ran into chaplains of other denominations which they had served alongside,

and which they might never see, much less work with again. John Holman

reminisced about urgently throwing up sandbags alongside a priest to protect an

advanced dressing station before taking heavy fire, both in their shirtsleeves

in the Amiens heat. Many took part in the conferring of battalion colours, now

being brought over from England or being consecrated for the first time, in

drumhead services in Germany and Flanders. Others found themselves, in moments

of inactivity, thrown back to moments which they had pushed into the back of

their minds during the victory autumn. They saw faces. They recalled brief,

intense, often whispered confidences. They remembered the men they had helped,

many, to die. Percy Coulthurst, Ewen MacDonald, Thomas McCarthy, Canon Scott

just out of hospital in England and W.H. Sparks flashing back to ministering,

stretcher to stretcher, reciting, “The Lord is my Shepherd”.

For many

chaplains with the Corps, the end of combat meant the pressure to get letters

written, some perhaps which they probably had wished to avoid. Murdoch found

himself awash in letters of sympathy to kinfolk in Canada. His Montreal

battalions, Highlanders, and working men left widows and orphans, bereaved

parents who needed some reassurance and comfort. Their men had died well,

suffered little, and had the ministrations of the priest or minister they

needed and deserved in the hour of their death. On their return, more than one

followed the example of George Kilpatrick, by 11 November the Senior Chaplain

of a Division, who personally visited the homes of every soldier from the 42nd

Battalion who had died overseas. As harrowing is that could be, there were some

consolation for padres, as more than one family was grateful for every scrap of

news about their loved one they could provide. They were touched, and often

inspired by another kind of bravery and resolute courage they witnessed among

those who had only waited, and waited.

chaplains with the Corps, the end of combat meant the pressure to get letters

written, some perhaps which they probably had wished to avoid. Murdoch found

himself awash in letters of sympathy to kinfolk in Canada. His Montreal

battalions, Highlanders, and working men left widows and orphans, bereaved

parents who needed some reassurance and comfort. Their men had died well,

suffered little, and had the ministrations of the priest or minister they

needed and deserved in the hour of their death. On their return, more than one

followed the example of George Kilpatrick, by 11 November the Senior Chaplain

of a Division, who personally visited the homes of every soldier from the 42nd

Battalion who had died overseas. As harrowing is that could be, there were some

consolation for padres, as more than one family was grateful for every scrap of

news about their loved one they could provide. They were touched, and often

inspired by another kind of bravery and resolute courage they witnessed among

those who had only waited, and waited.

One of the

most perceptive padres to write his superiors in this period was A. B.

MacDonald, a priest who would return to his Calgary church and devote his life

to veterans after the war. He had spent days among the refugees who streamed

back during the last weeks of the German retreat, hearing pitiful tales of

deprivation and atrocity. He had been only a few miles from Mons when his

gunners ceased firing on the 11th. As he looked around him, at the

devastated land and lives, and contemplated his own men coming back seeking

order out of chaos at home, he knew he needed help.

most perceptive padres to write his superiors in this period was A. B.

MacDonald, a priest who would return to his Calgary church and devote his life

to veterans after the war. He had spent days among the refugees who streamed

back during the last weeks of the German retreat, hearing pitiful tales of

deprivation and atrocity. He had been only a few miles from Mons when his

gunners ceased firing on the 11th. As he looked around him, at the

devastated land and lives, and contemplated his own men coming back seeking

order out of chaos at home, he knew he needed help.

MacDonald

reached out to J.J. O’Gorman, the doughty priest who lit the fuse which

exploded in Ottawa and led to reform of the Catholic chaplaincy, now returned

to direct the Catholic Army Huts overseas. He asked for copies of popular and

influential tracts by Catholic authorities on social questions, family life and

the pronouncements of Leo XIII on the church’s role in society. He intended to

translate, rewrite and paraphrase their contents to adapt them to Canadian

conditions and Canadian veterans. “The practical application of social science

in Canada will be completely different from England”, he noted. Lt. Col. W.T. Workman,

in London, ensured that he would have Rome leave.

reached out to J.J. O’Gorman, the doughty priest who lit the fuse which

exploded in Ottawa and led to reform of the Catholic chaplaincy, now returned

to direct the Catholic Army Huts overseas. He asked for copies of popular and

influential tracts by Catholic authorities on social questions, family life and

the pronouncements of Leo XIII on the church’s role in society. He intended to

translate, rewrite and paraphrase their contents to adapt them to Canadian

conditions and Canadian veterans. “The practical application of social science

in Canada will be completely different from England”, he noted. Lt. Col. W.T. Workman,

in London, ensured that he would have Rome leave.

By the

summer of 1916 MacDonald was back at Sarcee Camp in Calgary. He noted to A.L.

Sylvestre, his Senior Chaplain in Canada, that the veterans would open up and

trust the uniformed padre, or one they had known overseas. He recommended that

the Permanent Force be granted permanent chaplaincies. Sylvestre was

sympathetic, but Ottawa was already preparing the demise of the Chaplain Service.

MacDonald was probably the last chaplain standing on the day it was officially demobilized

— 1 January, 1921. The Great War was really over: now came the Peace to

endure, and overcome.

summer of 1916 MacDonald was back at Sarcee Camp in Calgary. He noted to A.L.

Sylvestre, his Senior Chaplain in Canada, that the veterans would open up and

trust the uniformed padre, or one they had known overseas. He recommended that

the Permanent Force be granted permanent chaplaincies. Sylvestre was

sympathetic, but Ottawa was already preparing the demise of the Chaplain Service.

MacDonald was probably the last chaplain standing on the day it was officially demobilized

— 1 January, 1921. The Great War was really over: now came the Peace to

endure, and overcome.